André Bazin, The Realist And The Expressive

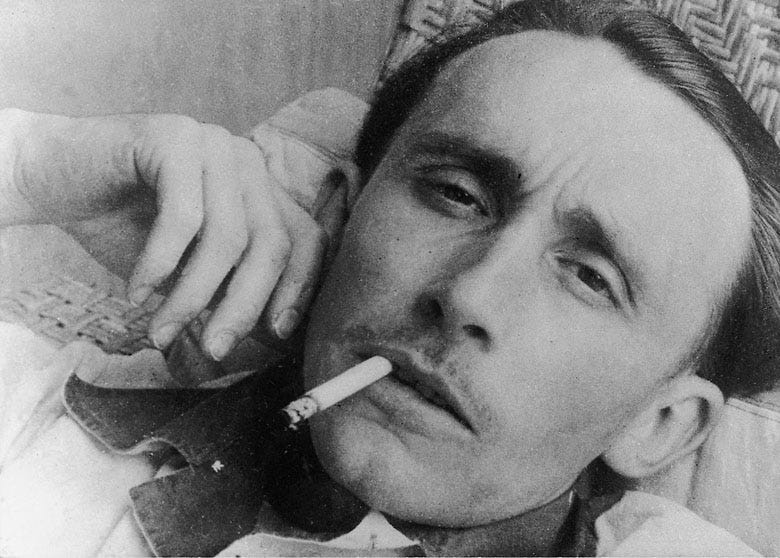

André Bazin, born 1918, was a failed french teacher with a stammer. During the German occupation of Paris, Bazin founded a ciné club. He would go on to become an extremely influential film critic and theorist. In 1958, Bazin passed away at the age of 40 from leukaemia.

In the 1940’s, when Bazin first became active in film criticism, it was reasonable that a person could go back and watch the majority of popular films without too much hassle. This gave Bazin a unique edge over any modern writer, as he knew pretty much all there was to know at the time. Bazin also bemoaned the state of french cinema, believing it was too ‘uppity’. As far as he was concerned, film should be reflective of the director’s true intentions. This led him to come up with a theory that there were two types of cinema; expressive and realist.

Bazin strongly disliked ‘expressive’ cinema. Expressive cinema could include German expressionism, Soviet montage, and many other forms of cinema. Bazin characterised it as film that used its unique power to manipulate the audience into thinking about and interpreting the film for themselves. For Bazin, the lack of autonomy was what made this type of cinema so unlikable.

Realist cinema, on the other hand, is entirely characterised by the autonomy of the audience. ‘Cinema Verité’, as it was often known, involved film with long takes, deep focus, natural lighting, straight editing, naturalistic performances, and non-professional actors. Verisimilitude is the key word here. The phrase Bazin would have used is ‘cutting with their eyes’, decribing the way that a realist film would allow a member of the audience to create their own cuts as they decided what was important and what should be focused on. Essentially, they should be able to create their own individual experience out of any given film. Bazin’s strive for ‘pure’ and ‘honest’ cinema would lead to the french new wave in the 1950’s, also spurred on by the development and popularisation of handheld cameras.

The way this ties in to Buster Keaton, then, is that he (unknowingly) used both expressive and realist filmmaking in his films. The point wasn’t to strive for some kind of pure cinema for him, it was to do whatever he thought would make his films funniest. If that meant an expressive element such as giving the audience a wink-wink here or there, he’d do it. Similarly, if this meant using a wide shot and not cutting for a while, he’d do that too. It was about serving the story, and most importantly, the gag.